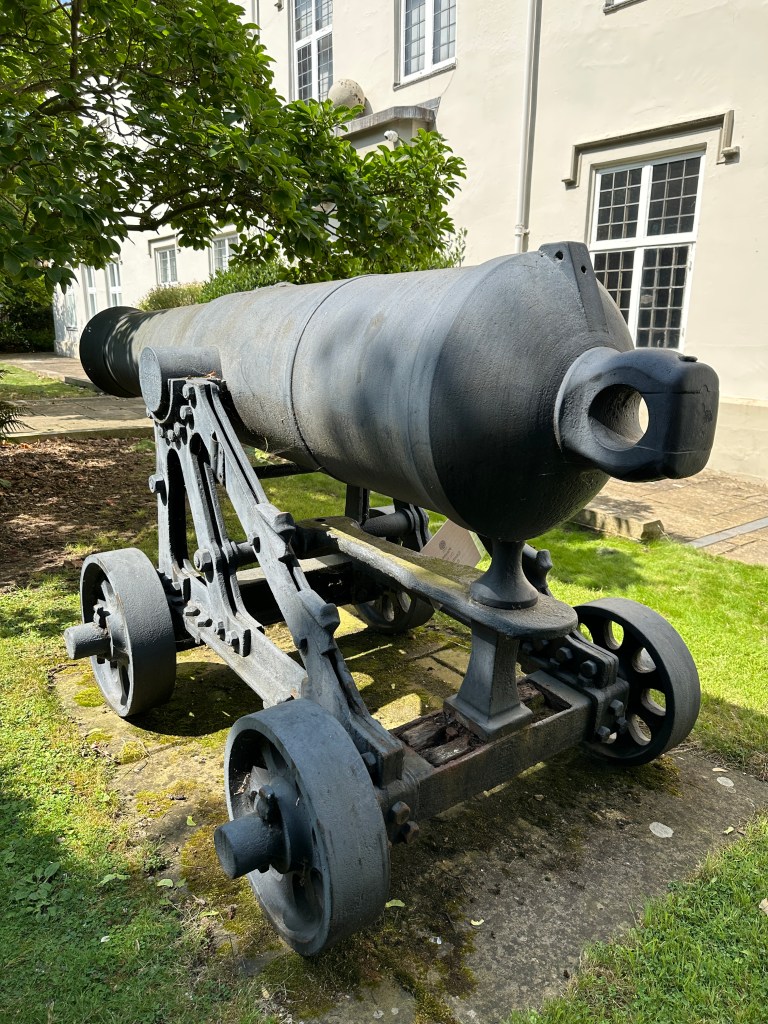

This gorgeous photo was taken in 2022, shortly after the current Russian invasion of Ukraine. Draped in flags of protest and spewing flowers of peace it made a poignant and moving statement. The old iron remnant of past wars can still carry a message in modern days, albeit quite different to any nineteenth century interpretation.

But, back to the history.

The trophy guns, including the Ely cannon, were captured by the Allied armies following the Siege of Sevastopol, or Sebastopol as the British then called it. The siege was part of the Crimean War of 1854 – 56. Queen Victoria is reputed to have shown great personal interest in the army. This painting depicts her visiting wounded soldiers at the military hospital at Chatham in March 1855.

The Crimean War included the battles of the Alma, Inkerman, and Balaclava which included the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade; and the Siege of Sevastopol. There were, in addition, two other theatres of war – in the Baltic with the Battle of Bomarsund and in the North Pacific with the Siege of Petropavlovsk.

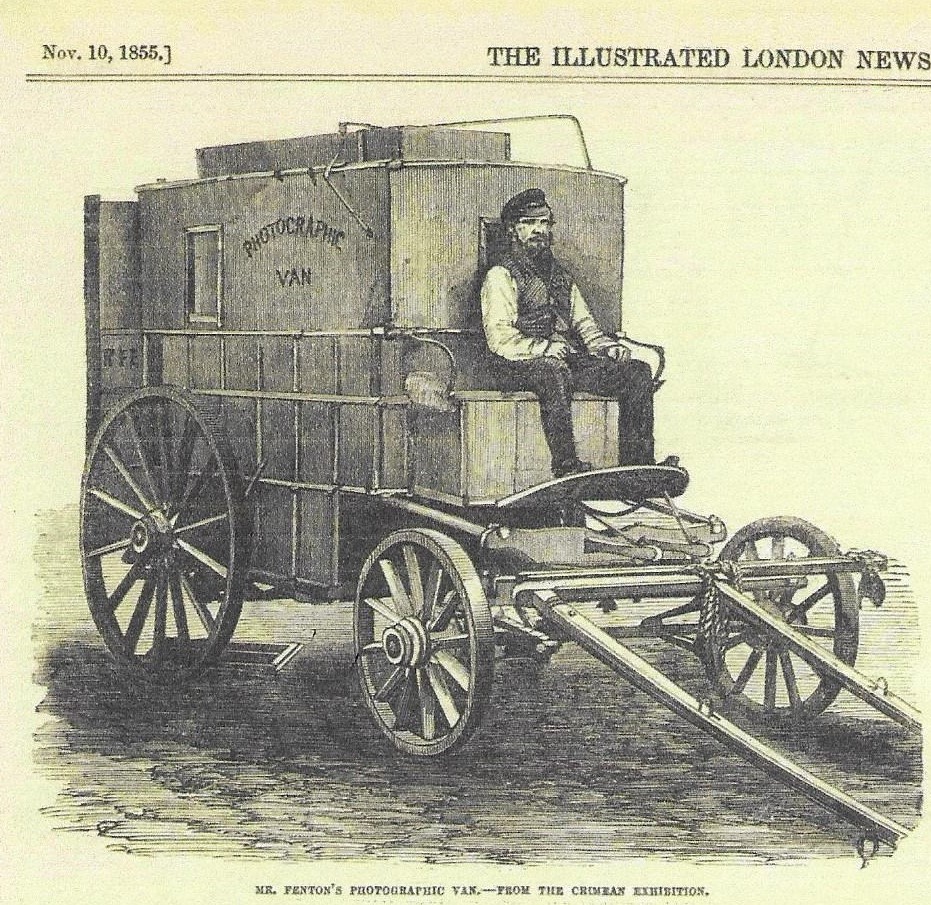

Crimea was the scene of the ground breaking hospital work of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. It was the last war in which British army officers went into battle wearing full dress uniform. It was the first war to make significant use of trenches (or ‘entrenchments’). The Crimean War was the first war to be widely reported at home thanks to the journalism of war correspondent William Howard Russell. It was also the first war to be recorded visually by Roger Fenton and a few other pioneering photographers – photography was still in its infancy.

Public awareness and outrage at the appalling conditions; the incompetent supply of food, clothing etc; and the huge death toll (nearly four times as many men died from disease as died as a result of combat) led to a government enquiry into the war.

Russia had annexed Crimea from the Ottoman Empire in 1784 and the Empress Catherine (aka Catherine the Great) ordered a fortress to be built at Sevastopol. Then, as now, Russia wanted the harbour as a base for its Black Sea fleet. One can imagine that large orders for iron cannon would have been placed for the expanding fleet and for the new fortress. Our Ely cannon, dated 1802, fits the bill.

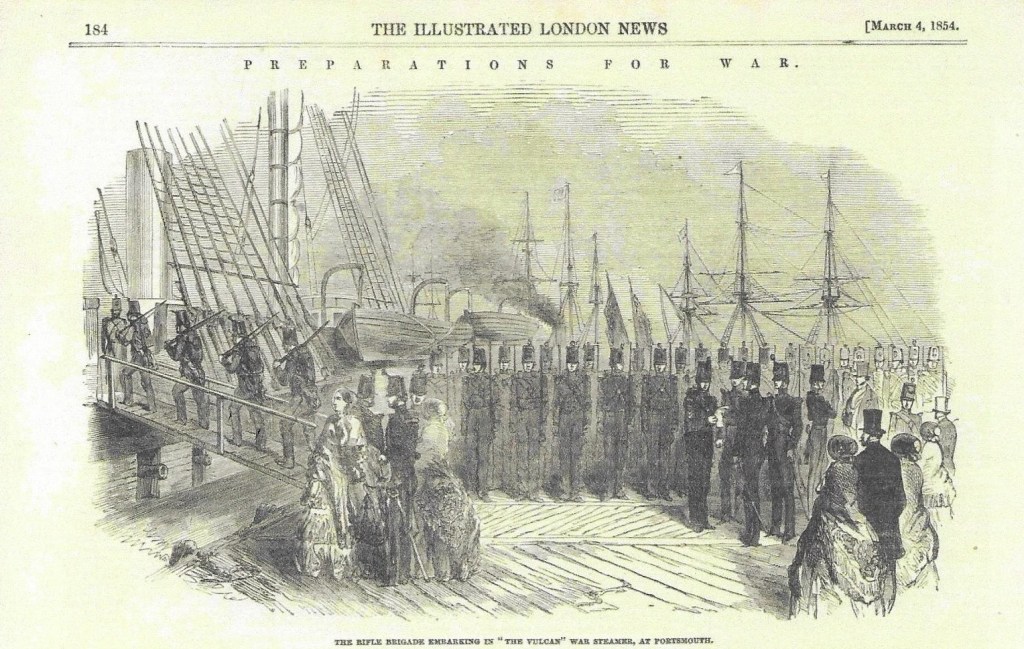

By the 1850s, the Ottoman empire (centred on Turkey) felt threatened by Russian expansion and needed support. Britain did not want to see the Russian navy grow strong enough to threaten its trade routes (Britannia ruled the waves in those days). And France was seeking to re-establish itself after the Napoleonic Wars and had its own agendas. New allies Britain and France, with the tacit agreement of the other major European players, Austria and Prussia, set out to support Turkey. There were Allied boots on the ground of Gallipoli in spring 1854.

Very few wives were permitted to travel with the troops. The Illustrated London News reported the following story alongside the image above: ‘The wife of a private being prevented going out by the regulations of the service, dressed herself in Rifle costume, and, gun in hand, actually marched into the Dockyard. She was, however, detected on getting on board; but we hear that permission to go out with her husband was granted to her.’ Let’s hope the story had a happy ending.

By the time the allied forces of Turkey, Britain, and France arrived outside Sevastopol the gun that would become our Ely cannon was over 50 years old. The very latest cannon would have had rifling which improved their accuracy but our gun was old-style, smooth bore. With the arrival of the Allies, its quiet life on the battlements looking out over the harbour was about to change.

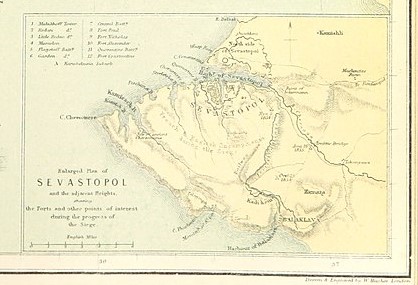

The Russians seem to have woken up quite late to the Allied threat to Sevastopol. Enter the military engineer, Lt Col Totleben. He initially focussed on strengthening the Star Fort defences to the north of Sevastopol. However, when the Allies took up positions to the south, Totleben set to work to turn what were little more than walls and mounds of loose earth and rubble into an extended system of defences four miles long. One of the Russians’ defensive actions was to sink many of their ships in order to block the entrance to the bay and prevent the British navy getting in. Before sinking them, they brought the ships’ cannon ashore and used them in the newly created land defences. This explains why so many of the Russian trophy guns brought back to Britain in 1856 were navy guns.

Part of an album of paintings showing scenes from the siege of Sevastopol 1854-55 and exposed at the 1872 Moscow Polytechnic Exhibition. Royal Collection Trust RCIN 2500585

The Siege of Sevastopol began in October 1854 with the Allied armies entrenched on the south side of the town. The Russians were able to re-supply from the north so never ran short of ammunition. The two sides bombarded each other for nearly a year. It wasn’t until September 1855 that things changed. By then, the British navy had managed to cut the Russian supply lines across the Sea of Azov. Following a new, major bombardment of the town (the sixth bombardment), French troops successfully stormed the Malakoff fort and the British attacked the Redan. It gradually became apparent that the Russians were evacuating the town, crossing a pontoon bridge over the bay to the north side, but first destroying as much of their abandoned supplies and equipment as they could. No army leaves usable materiel for the enemy if it can be helped. In Sebastopol Sketches, Tolstoy (who had served in the Russian army at Sevastopol) paints a vivid picture of the scene: ‘Without warning, a series of flashes leapt along the ground between the 1st and 2nd bastions; explosions shook the air, illuminating strange black objects and flying stones. Down by the docks something was on fire, and the red flames were reflected in the water. The pontoon bridge, packed with people, was lit up by the glare from the Nicholas battery. On the distant headland where the Alexander battery was situated, a great sheet of flame seemed to be hanging above the water, illuminating the base of the smoke-cloud that had formed above it.’

A few photographs exist of the destruction that the Allies found when they entered Sevastopol. We can conjure a romantic image of our gun lying amongst the debris beside its shattered carriage. However, there is a more mundane possibility. Amongst the military materiel taken by the Allies were ‘3,000 pieces that had not been mounted‘. It is possible that, already old, our Ely cannon sat out the siege in a rusting heap of spares. We can never know exactly what happened except that the gun that would become the Ely cannon was considered by someone to be worth saving and shipping back to Britain.

The war was estimated to have cost the lives of more than twenty-one thousand British soldiers – and even this was less than a twelfth of the total number dead. The largest number of casualties were undoubtedly Russian with some estimates that, on September 8th alone, 18,000 Russian soldiers died. The statistics are obscene, but they are supported by equally dreadful eyewitness accounts of the piles of Russian bodies that British soldiers found when they first entered the town.

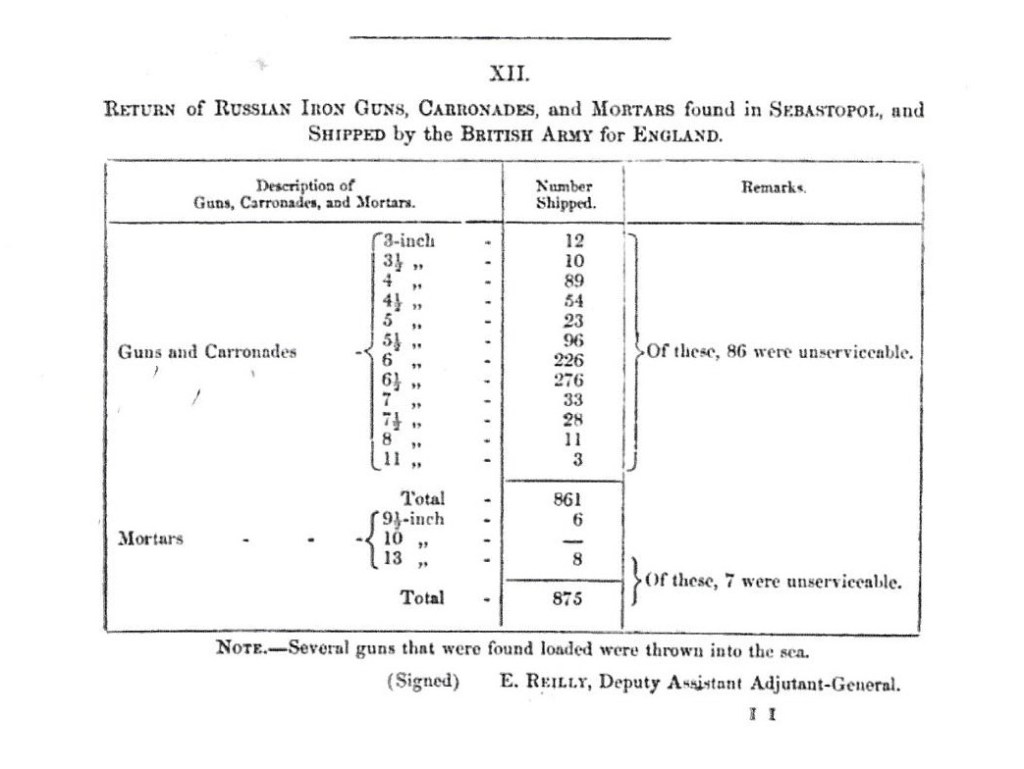

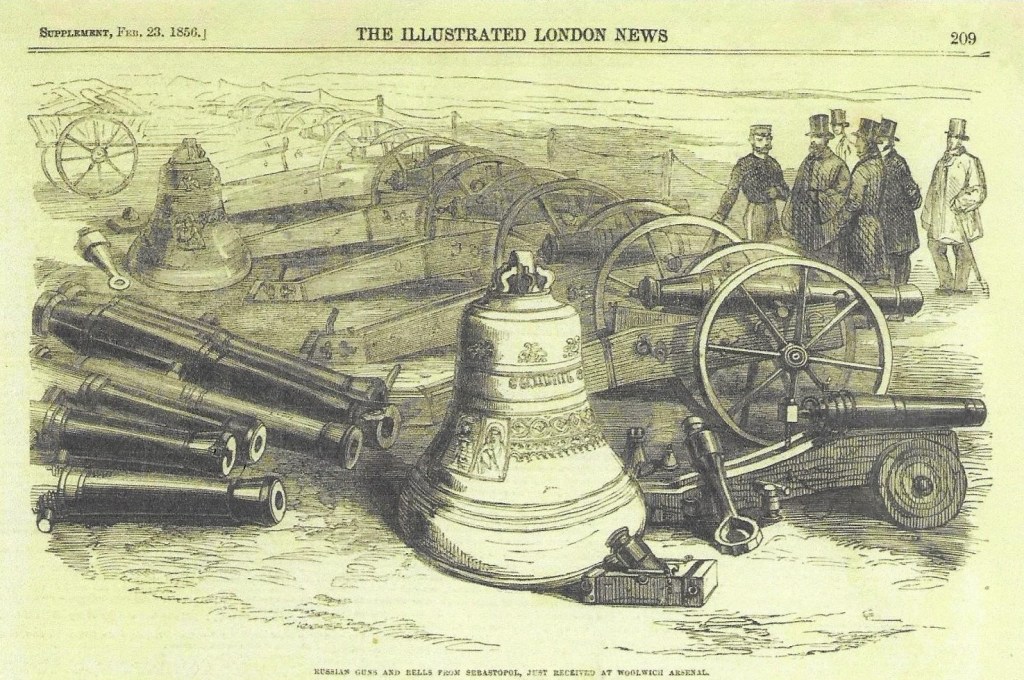

The Crimean War ended with the Treaty of Paris in March 1856 but it was summer before the British army was at last able to sail for home. This was a huge logistical task in itself but there was another problem – what to do with the captured Russian materiel? This was divided amongst the Allies according the number of troops each had contributed to the war. The French had the largest share of the booty and did not hesitate to ship it back to France. One option discussed by the British was to dump it all at sea but, eventually, it was decided to bring some items back to Britain. Some sources list thousands of guns shipped to Britain, and there were undoubtedly thousands taken at Sevastopol. However, Captain, Royal Artillery, and Brevet Major W.E.M. Reilly, who had been Brigade-Major of the siege train at the end of the war, accounts for 861 guns and carronades ‘Shipped by the British Army for England‘. Our Ely cannon is 6½ inch, one of the 276 guns of that bore listed by Reilly.

At first, no-one knew what to do with the trophies and they lay rusting at Woolwich. But then, in January 1857, the decision was taken that the guns could be distributed. Nearly 300 guns were distributed to towns and cities including in the Dominions.

The story of the Russian trophy guns doesn’t quite end there. Some of the guns, like Ely’s, became part of the fabric of their new homes. Some were less welcomed and relegated to forgotten corners. Many were melted down during World War II for the war effort. There is an excellent database showing where the guns ended up, and how many of them are still there to be visited including in Canada, Australia, Gibraltar, and across the UK and Ireland (see the Osborne House and Silverhawk links below).

Sources:

Tolstoy, Leo – The Sebastopol Sketches, first published 1856, this translation first published 1986, Penguin Books

Hibbert, Christopher – The Destruction of Lord Raglan, first published 1961, Longmans

Reilly, W. Edmund M. – An Account of the Artillery Operations conducted by the Royal Artillery and Royal Naval Brigade before Sebastopol, 1859

Find out where the trophy guns are now https://www.osborne.house/profilego.asp?ref=2C3931

The Illustrated London News, various dates

The National Army Museum has some great pages on the Crimean War https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/crimean-war

For photos of the guns in Canada https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/artillery-in-canada-russian-crimean-war-trophy-guns