The Ely cannon touched the lives of many people from the day it was cast to its arrival in Ely. Here are some of the more colourful characters: Charles Gascoigne’s family including Elizabeth Primrose Gascoigne, her husband George Pollen, and Gascoigne’s second wife Anastasia Jessye Guthrie; William Marshall of Ely; Lord Hardwicke; and the bandmaster, Daniel Godfrey.

Charles Gascoigne’s Family

When Gascoigne left Scotland for Russia in 1786 his son, Charles, was 21. I have not been able to trace him. However, there is a record of a Charles Gascoigne in New York in 1819 – did young Charles put as much distance between himself and his father (and his father’s creditors) as possible and seek a new life in America? Gascoigne’s daughter Anne had just married Lord Haddington but his other daughters were still young: Mary was 14 and Elizabeth Primrose just 11 years old. Presumably they and their mother joined Gascoigne in Russia. I haven’t found a record of his wife’s death but, by 1797, Gascoigne was free to re-marry which he did, extraordinarily, to the 15 year old Anastasia Jessye Guthrie in 1797 (see below).

Anne and Mary Gascoigne

Anne married Thomas Hamilton, 7th Earl of Haddington, in 1786 when she was 24 and he was 66. She was Haddington’s second wife – he already had a son and heir from his first marriage. According to Histories of the Scottish Families (1889), there was significant hostility to the match but the earl was ‘too much in love’ to be dissuaded. We’re told that the only fault the earl could find in Anne was her ‘warmth of temper’. How wonderful to find something about her character! Anne was, perhaps, what we would call today, feisty. Their daughter, Charlotte, was born in 1790 but sadly died aged 3, followed, in 1794, by the earl. The earl’s son, now the 8th earl, is quoted as writing that he intends to ‘behave to my father’s widow with kindness’. Let us hope that he did. When arranging his father’s funeral, the new 8th earl wrote that he would invite Lord Elphinstone, a ‘cousin german once removed’ of Lady Haddington’ but not any of her other relations or ‘clamjamfrey’ [contemptuous Scots word for riff-raff].

In 1796 when she was aged 35, Anne married James Dalrymple of North Berwick. North Berwick is close to Haddington and becomes a significant place in the lives of the Gascoigne girls. Anne’s marriage to Dalrymple took place in St Petersburg which suggests that Anne took her betrothed to meet her father, Charles Gascoigne. The wedding must have been splendid!

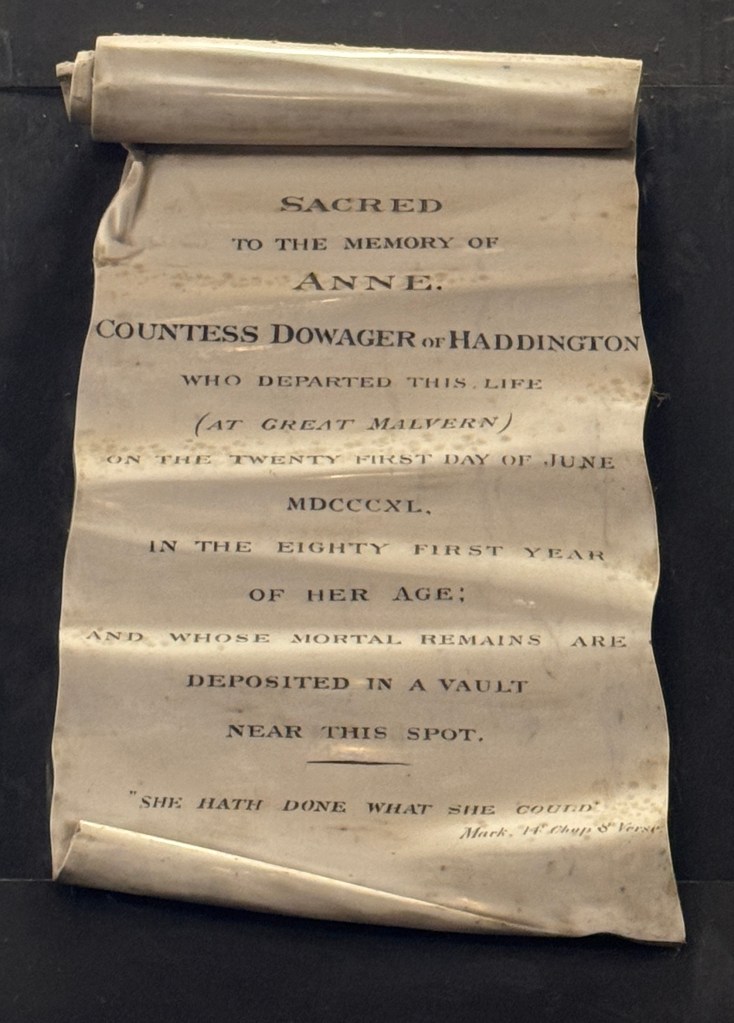

Anne died at Great Malvern on midsummer’s day 1840 and there’s a memorial to her in Great Malvern Priory (aka the Abbey). To a modern reader the bible quotation (Mark 14 verse 8) looks rather sad: ‘she hath done what she could‘ sounds as if she could perhaps have tried harder. However, Victorian readers would probably have understood it to mean that she had done everything that she possibly could.

Meanwhile, sister Mary had married Russian General Alexander Markovich Poltoratsky. However, Mary died in 1795 leaving the general with three small children including the one year old Maria Alexandrovna Poltoratsky. Little Maria may have become close to her aunt Elizabeth Primrose at this time – she would later be a significant beneficiary of Elizabeth Primrose’s will. However, when Maria’s Aunt Anne came to St Petersburg in 1796 to be married, her life was about to change. One can only imagine how Anne felt having lost her own daughter at the age of three – here was her motherless niece of about the same age. We can’t know how it was arranged but it appears that little Maria was brought up by the Dalrymples in North Berwick, her name being anglicised to Mary Augusta Dalrymple. What a kind man James Dalrymple must have been! It wasn’t a formal adoption as we know it today – when ‘little Maria’ herself married in North Berwick in 1817 her name was given as Mary Poltoratsky.

Memorials of the Earls of Haddington in Histories of Scottish Families, vol 1 by Sir William Fraser, 1889, digitised by National Library of Scotland

Elizabeth Primrose Gascoigne and George Augustus Pollen

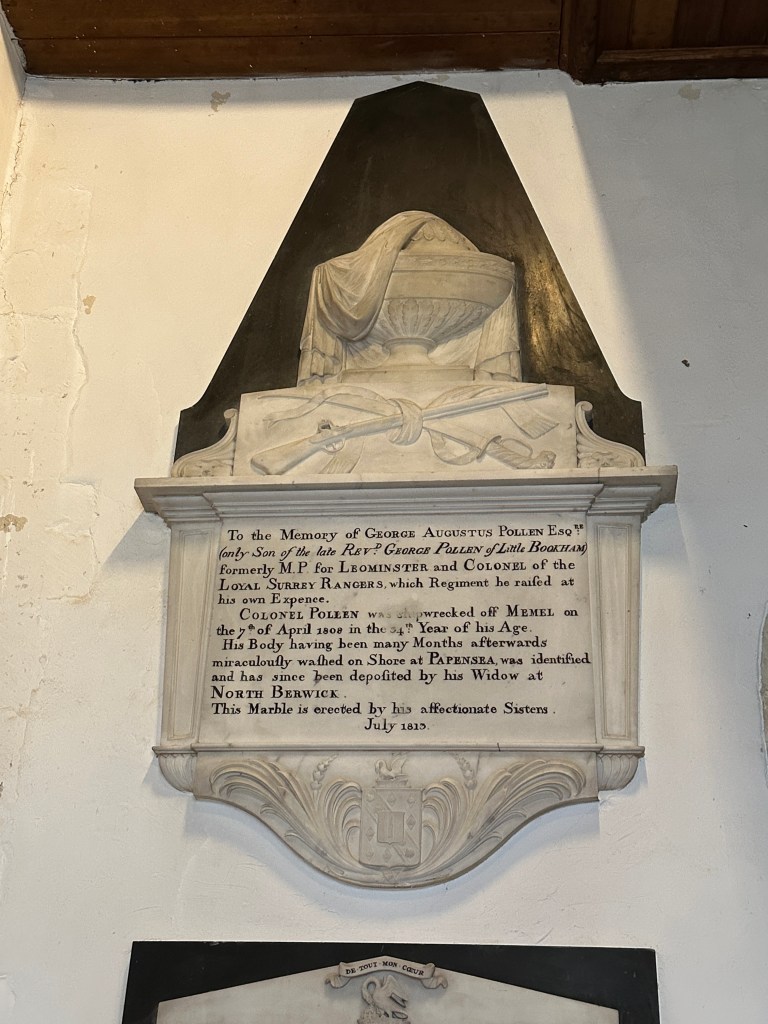

The History of Parliament Online website gives us a short biography of Pollen. Educated at Eton and Cambridge he was heir to a fortune. He tried his hand in parliament, where he seems to have made himself unpopular with his outspoken views, before becoming a cavalry officer. In 1799 he raised a fencible regiment (a regiment for the purpose of defence), the ‘Loyal Surrey Rangers’, at his own expense. Commissioned Colonel of the regiment, Pollen was posted with them to Nova Scotia in 1800. Returning in 1802 and with no further prospect of a parliamentary career, Pollen went travelling on the continent. He was once described as ‘a man who once attempted to play a part in the House of Commons and did distinguish himself there, as elsewhere, by his most consummate effrontery.’ In a letter dated Jan 28th/ Feb 9th 1803 Pollen wrote to a friend, “I have found my wife – I was married to Miss Gascoigne a few days ago and am as happy as all men should be in the infancy of domestic comforts and as I pray God I may be in its old age.” Sadly, the gorgeous George Pollen was lost in a terrible shipwreck off the coast of Lithuania in 1808.

Elizabeth Primrose was travelling with her husband when their ship, Agathon, went down. The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1811 gives an extraordinarily detailed account of the shipwreck. Elizabeth Primrose, with her ‘Cosaque’ boy servant, was one of the last to be rescued having endured three days on the wreck being lashed by the icy Baltic waves while other passengers and sailors were washed overboard. It’s well worth a read – see link below. George’s body was found some time after the wreck and was buried in North Berwick where, presumably, Elisabeth Primrose had sought refuge with her sister, Anne.

In a curious twist (for our story), another of those lost in that wreck was Viscount Royston, elder son of the Earl of Hardwicke. The earl’s younger son, Charles Yorke, later became the same Lord Hardwicke that Ely solicitor H R Evans wrote to in 1860 requesting a Crimean war cannon for Ely.

In his will, George left a considerable inheritance. One bequest gives a clue as to George’s bachelor lifestyle – he made a bequest of £1,000 to his friend William Brummell, almost certainly the elder brother of the famous George ‘Beau’ Brummell who was an intimate friend of the Prince Regent.

Most of George’s fortune was left to his widow, Elizabeth Primrose. However, it appears that the head of the family, Rev George Pollen, was able to buy her out thus keeping the Pollen estate intact. In later life, Elizabeth lived in some style in a house on Wimbledon Common where she kept her own carriage and horses. She died in 1858 and is buried in St Mary’s church, Wimbledon. Her will specifies that the horses should be well treated. She had never remarried and desired that, if she died in Scotland (presumably visiting Anne), she should be buried with her beloved husband in North Berwick. Shares in the Carron company seem to have formed a significant part of Elizabeth’s fortune – we can deduce that Charles Gascoigne divided his Carron shares between his children before he was declared bankrupt and had to leave the country! Among the bequests in Elizabeth’s will she describes a special brooch – an ‘enamelled Sevigne set in diamonds’. Given her father’s close connections with the Russian royal family, it may have been a spectacular piece in the style of Romanov jewellery.

https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/pollen-george-augustus-1775-1808

https://www.thepollenestate.com/about-us/history/freehold-ownership

The Loyal Surry Fencibles, 1798 – 1802 – article by W.Y.Carman published by the Society for Army Historical Research vol 62 no 250 pp118-119

G A Pollen to Julien Niemcewicz, January 28th 1803. Manuscript. From Special Collections Research Library and Archive, Kean University, Liberty Hall Collection 1800s. https://digitalcommons.kean.edu/lhc_1800s/236/

The Gentleman’s Magazine 1808 p461 (Pollen’s obituary) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027527467&seq=493&q1=Pollen

The Gentleman’s Magazine 1811 p541 – 543 (the shipwreck) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081674487&seq=579

Anastasia Jessye Guthrie

In 1797 Anastasia married Charles Gascoigne at the British Chaplaincy, St Petersburg. She was then aged 15 while Gascoigne was 60. Both her parents were living. Born in St Petersburg in 1782, Anastasia was the daughter of a doctor, Matthew Guthrie MD of Hawkerton. Guthrie went to Russia in 1769, initially as physician to the 1st and 2nd Imperial Corps of Noble Cadets. He became a personal Councillor to Tsar Alexander 1st and his wife Empress Elizabeth. In 1782 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. Guthrie’s wife and Anastasia’s mother was Marie Dunant (nee de Romaud-Survesnes) who was at one time Acting Director of the Imperial Convent for the Education of the Female Nobility of Russia. They had two daughters, the elder being Anastasia. One might assume that Anastasia and her parents calculated that the wealthy Gascoigne would not live long. However, I have come across another possibility. Apparently there was court gossip that the beautiful Anastasia had become the mistress of the father of Tsar Paul’s favourite, Anna Lopukhina. The marriage with Gascoigne could have served to save Anastasia’s reputation as well as make her a wealthy woman. Gascoigne lived nine years after the marriage, dying in 1806. The following year Anastasia married again, this time to Thomson Bonar, and went on to have nine children with him. Anastasia died in 1855. Her name appears on the Bonar memorial in the churchyard of St Nicholas church, Chislehurst where we also find the curious information that, in 1813, Thomson Bonar’s parents had been murdered in their bedchamber by a servant!

https://btw.wlv.ac.uk/authors/1064 Article by Dr Benjamin Colbert about Marie Dunant, Anastasia’s mother

https://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/records/monumental-inscriptions/chislehurst

Cross, Anthony – By the Banks of the Neva: chapters from the lives and careers of the British in eighteenth century Russia. CUP 1997

William Marshall and the ‘Battle of the Pews’

When the Russian Trophy Gun was paraded through the streets of Ely in June 1860, the man riding at the head of the ‘principal inhabitants’ was William Marshall. This may have been to the annoyance of one William Harlock.

Born in 1815, Marshall was an attorney and solicitor like his father before him. The family home was number 23, Fore Hill, Ely. The house is still there, showing a shop front with entrance plus a separate front door. It is likely that the professional business was transacted downstairs while the family lived above.

In the early 19th century, ‘local government’ was in the hands of the parish vestry who set the Poor Rate and the Church Rate and were responsible for the health and well-being of their community. Marshall was a member of Ely Holy Trinity vestry, the larger of the two Ely parishes. Marshall became Clerk to the Guardians of the Poor, Superintendent Registrar of the Ely Union (the workhouse), and held the post of coroner for the Isle of Ely for forty years. He was also Clerk to the Burial Board. J.H. Clements wrote: “No epitaph can be placed upon a tomb or gravestone until it has received the sanction of Mr Marshall; this course the Burial Board felt itself compelled to adopt in consequence of absurd people selecting absurd tributes to the memory of their relatives.” Priceless!

But what of the character of William Marshall? His actions suggest a very clever man who was able to argue a point cogently and persuasively, a man of high principles who was secure in his ability to wield influence, perhaps even control, but without seeking self-glorification.

Marshall’s abilities as an attorney were demonstrated in 1858. The Churchwardens brought a case against Louis David Cugny who had a grocery business in the High Street and who refused to pay the Church Rate. The grocer engaged a London lawyer to present his case. Marshall acted for the Churchwardens. One can imagine that the London lawyer may have underestimated his provincial opponent. After much legal argument, the court ordered that the grocer should pay.

And then, of course, there is the ‘Battle of the Pews’! The parishioners of Holy Trinity worshipped in the Lady Chapel of the cathedral. By the mid 1850s it was agreed that the chapel needed refurbishment and also that extra seating was required given the growth in population. The existing pews had been installed in 1806 and those at the front had been paid for by wealthier parishioners. The rights to these private pews had been handed down through generations with the result that, at many services, those pews were almost empty whilst ‘the poor’ were crowded in at the back. Plans were drawn up that would increase the seating capacity. So far, so good, but there was more to it than that. In addition to concerns that the plans were too ‘Romish’ (high church), Marshall was keen that the church should become a ‘free church’ where no-one had the rights to a particular seat and anyone could sit anywhere. He felt so strongly that he gave up his own seat (though not until January 1864 when the case was almost won). Although most parishioners seem to have agreed with Marshall, William Harlock most certainly did not. Harlock made it clear he wanted to retain his seat. From their letters to newspapers, Harlock comes across as reactionary and resistant to change, vigorously defending against the perceived threat to his status. Marshall’s reasoned arguments, always backed up by figures and sometimes under-pinned with veiled threat, must have angered Harlock to boiling point. The Marshalls and the Harlocks had been near neighbours on Fore Hill and, who knows, there may have been animosity going back generations? More plans were drawn up, committees formed, votes taken, and more acrimonious letters published in the press. At last, in May 1864, plans were taken to the Diocesan Consistory Court in Cambridge. There, Harlock argued for retaining the private seats while Marshall argued that all seats should be free. Unsurprisingly, Marshall won the day. After a decade of argument, work started on removing the old pews in the Lady Chapel a few days later.

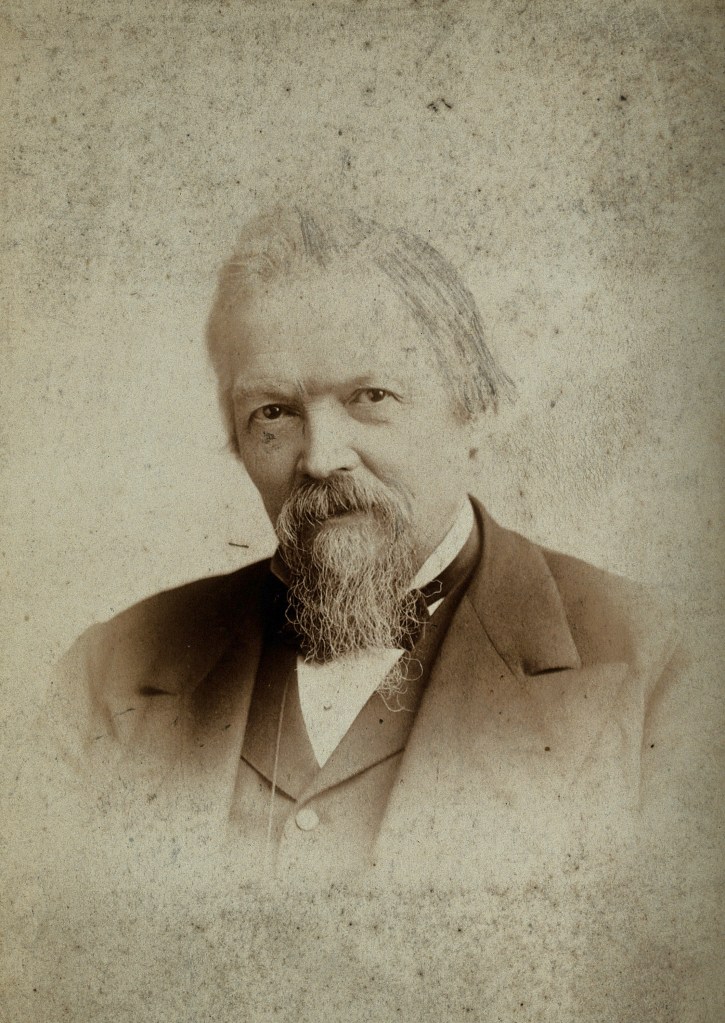

By 1871 Marshall had relocated from the relatively humble premises on Fore Hill to the elegant Hill House on Back Hill, now part of the King’s School. This may have been at the time of Marshall’s marriage to Julia Durham in 1853. In later life he accepted some more prestigious positions, becoming President of the Ely Horticultural Society and, in 1879, President of the Cambridgeshire and Isle of Ely Chamber of Agriculture. He died in 1890.

The Marshalls were an intellectual family. William’s younger brother, John, became a teacher of anatomy and Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, and the youngest brother, Charles, became Rector of Moston in Lancashire. William himself was, in addition to his professional and civic activities, a respected botanist.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Life of John Marshall, mentions William https://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/client/en_GB/lives/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ASSET$002f0$002fSD_ASSET:372396/one?qu=%22rcs%3A+E000209%22&rt=false%7C%7C%7CIDENTIFIER%7C%7C%7CResource+Identifier

Hall, Shirley – Holy Trinity Ely 1566 – 1938, published 2022

Clements, J.H. – A Brief History of Ely and neighbouring villages in the Isle, 1868

Charles Yorke, 4th Earl Hardwicke

The Cambridgeshire Chronicle tells us that the Ely cannon was requested by Mr Evans (an Ely solicitor) through Lord Hardwicke. Lord Hardwicke was Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire and Commander in Chief of the Cambridgeshire Militia. Clearly, he was the person to approach to apply for a trophy gun to mark the creation of the Ely Rifle Volunteers. It was not long before Evans heard from the War Office that the request had been approved.

The 4th Earl had had a long career in the navy retiring with the rank of Rear Admiral but, leaving aside the redoubtable Earl’s career and achievements, there are some stories that paint quite a picture of the man.

Lord Hardwick is reputed to have fathered several illegitimate children by his servants. One of them was Charlotte Pratt who gave birth to a son, James Pratt, in 1848. Charlotte married the following year and there is a note in the marriage register saying that Charlotte’s employer, 4th Earl Hardwicke, was understood to have been the father of the child. It was said that the Earl arranged the marriage in return for a cottage and financial support for the child. There is also a quote from ‘Wimpole as I knew It’ by the Earl’s nephew, A.C.Yorke: ‘Charlotte … was a picture. The handsomest woman that I ever remember to have seen. In harvest time to see her swinging along the road with a bundle of corn balanced on her head, both arms akimbo, was a study in colour, figure and poise.’

A.C.Yorke also reminisces directly about his uncle, the 4th Earl, in ‘Wimpole as I knew it’. He describes ‘a domineering, masterful old man; with, at times, a very rough tongue. A martinet of the old school on his own quarterdeck – that describes him.’

Wimpole estate, now National Trust.

https://www.wimpolepast.org/register_marriages_1800.asp

https://www.wimpolepast.org/wimpole_as_i_knew_it.asp

Daniel Godfrey

Bandmaster of the Band of the Grenadier Guards and marching them proudly through the streets of Ely on 26th June 1860 was Daniel Godfrey Esq. Godfrey was educated at the Royal Academy of Music where he later became a professor of military music and was elected a fellow. He was appointed bandmaster in 1856 and one of his first duties was to play into London the Brigade of Guards returning from the Crimean War.

Godfrey’s father, Charles, was bandmaster of the Coldstream Guards. Could this explain why Ely got the ‘wrong’ band for the inauguration of the cannon? Did someone write to the wrong Godfrey? Did Charles Godfrey accept the invitation for the Coldstreams only to find that he couldn’t make the date and so delegated the honour to his son? We shall never know, but there is certainly scope for a mix-up!

Daniel Godfrey was also a successful composer. In 1863 he wrote the Guards’ Waltz for the ball given by the officers of the Guards for the Prince and Princess of Wales, later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. Hear the Guards’ Waltz via the Youtube link below for the sound of the 1860s.