Gascoigne was undoubtedly an extraordinary man and a hugely successful industrialist in Russia. Our Ely cannon was cast at Gascoigne’s Alexandrovsky Works in Petrozavodsk. Petrozavodsk is on the shore of Lake Onega, north of St Petersburg and close to the border with Finland. The works later became a tractor plant but the street outside is still named for Gascoigne (ulitsa Charlza Gaskoyna).

So how did a Brit end up making guns for Russia that would end up firing on British soldiers?

It was a militaristic age. Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, was expanding Russian territories and there was war with the Ottoman Empire for control of the Black Sea and dominance of the Near East. The American War of Independence had ended in 1783. The French Revolutionary Wars took place in Europe 1792 to 1799, leading to the Napoleonic Wars of 1800 to 1815. Britain and Russia were allies at this period.

When he left for Russia in 1786, could Gascoigne have guessed that, 70 years later, Britain would be fighting Russia in the Crimea? Probably not, but there is a line that can be drawn between selling arms abroad and actually assisting a foreign power to manufacture arms and it’s a line that Gascoigne appears to have crossed.

Gascoigne seems to have been a largely self-made man, a hugely ambitious and ruthless industrialist at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. His father, George Woodroffe Gascoigne, held a commission in the British army at the time of the Jacobite uprising of 1745. While still an Ensign, he married Grizel, the eldest daughter of the Scottish peer Charles, 9th Lord Elphinstone. Our Charles Gascoigne was the couple’s first born son but no records of his birth or baptism have been found. It is likely that Lord Elphinstone did not approve of his daughter’s marriage to such a junior officer. Little is known of Charles Gascoigne’s early life but there may have been very little money – could this have fed his driving ambition for wealth later in life? After the 9th Lord’s death in 1757 there appears to have been more contact with Gascoigne’s Elphinstone relations.

In 1757, Gascoigne met his future father-in-law Samuel Garbett, a Birmingham industrialist, and was found a partnership in a firm of drysalters (manufacturers of chemicals such as glue and dye) called Coney and Gascoigne. In 1759 he married Garbett’s daughter Mary at St Martin’s Church, Birmingham. In 1763 Garbett opened a turpentine factory at Carronshore, Falkirk, Scotland and brought in his son-in-law to manage the business. The business expanded to include shipping and in 1765 Gascoigne took over the lease of the Carronshore harbour and also became a partner at the Carron ironworks. Garbett’s company collapsed in 1772 with large debts which may have been due to Gascoigne’s financial dealings.

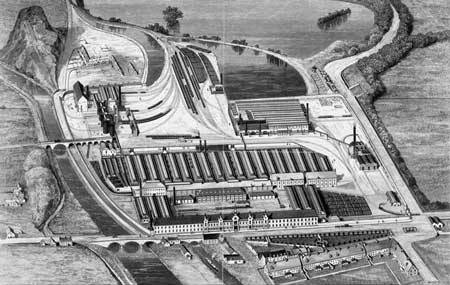

The Carron company had a contract with the Board of Ordnance for making long guns. However, these were of poor quality and the contract was withdrawn in 1773. Also in 1773, the company received an order from Russia for a pumping engine and a quantity of guns. At this time, Britain had a trade agreement with Russia. Gascoigne was determined to succeed and by 1778 a new gun, the carronade, had been developed. This gun had considerable success at sea especially during the Napoleonic Wars. Meanwhile Gascoigne’s private affairs had deteriorated and led to his bankruptcy. However, he continued as manager at Carron.

During this time, Gascoigne’s family had been growing. Anne was born in 1760 and Charles in 1765, then Mary in 1772 and Elizabeth in 1775.

In 1784, Carron received an order from Russia for 432 cannon. However, relations were now more strained between the two countries. When Gascoigne was found to be sending patterns, plans and instructions for casting the guns, he was called in by the Lord Advocate to explain himself. He was pardoned and it was agreed he could go to Russia in 1786 along with machinery that could be exported.

By now, Gascoigne’s house and other property had been sold and the family were living in a rented house. Bankrupt and pursued by creditors, Gascoigne could not refuse the opportunities offered in Russia. He set sail in May 1786, ostensibly to assist with setting up a foundry, taking with him a number of his own workmen. Although he had said he would return by winter, he negotiated a good salary and productivity bonus in Russia that suggested he had long term plans. When his contract was renewed in 1789 his salary was £2,500 compared with his replacement manager at Carron who received £700.

Gascoigne lived in Russia until his death 20 years later. He became head of all the mines and foundries in the Karelia region including the mines at Olonets. In addition, Gascoigne created a foundry at Luhansk in Ukraine where he is regarded as one of the founders of the city. He became known as Karl Karlovich Gaskoin and became a State Councillor (a member of the government), received the Order of Saint Anne 1st and 2nd class, and the Order of St Vladimir, the equivalent of a knighthood. The portrait below shows him wearing the cross of Saint Vladimir and the star of Saint Anne.

Gascoigne died at Kolpino, outside St Petersburg, in July 1806 and was buried in Petrozavodsk. The site of his grave has been lost. Over the years, Gascoigne’s reputation has fluctuated. He has been seen by the British as a traitor and in Russia during the soviet period as an industrial spy. However, in 2021 a huge new memorial to him was erected in Petrozavodsk which would, no doubt, have pleased him enormously.

Find out more about Gascoigne’s family

Sources:

Falkirk Local History Society is an exceptional source of information about Charles Gascoigne. Here are links to some of their material:

https://falkirklocalhistory.club/people/charles-gascoigne/

https://falkirklocalhistory.club/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/carron-in-the-east-17.pdf

Bara, J L – A Loose Cannon: Charles Gascoigne in eighteenth century Russia Falkirk Local History Society, 2019 Click to access loose-cannon-14.pdf

Watters, Brian – Where Iron runs like water: a new history of the Carron Works 1759-1982 published 1998